/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/31653645/90767909.0.jpg)

Three years ago, sex education advocates sat down to write national standards for how students learn about reproduction — something akin to the Common Core standards. Except, in this case, for sex.

The moment, in a way, seemed just right. Congress had effectively cut off federal funding for abstinence-only education in 2009. But no one knew quite what would, or should, replace it.

The result was the National Sexuality Education Standards, the first attempt at creating a road map for what skills and knowledge students should get from sex education. The new curriculum would be based on science, include clear information on safe sex practices, emphasize healthy relationships, and be LGBT friendly.

But so far, only one state, Colorado, has even come close to adopting them.

"There are pockets of good sex education," says Debra Hauser, president of Advocates for Youth, one of three sex education groups that joined to form the Future of Sex Education and write the standards. "But by and large we're still pushing."

The abstinence experiment

For 13 years — an entire generation of school kids — the federal government spent $1.5 billion telling students not to have sex.

From 1996 to 2009, states that took federal money for sex education were required to teach kids that the only acceptable time to have sex was in a heterosexual marriage, and that premarital sex was likely to have harmful effects. The percent of students learning about abstinence and not contraception grew from 10 percent in 1995 to 25 percent in 2006.

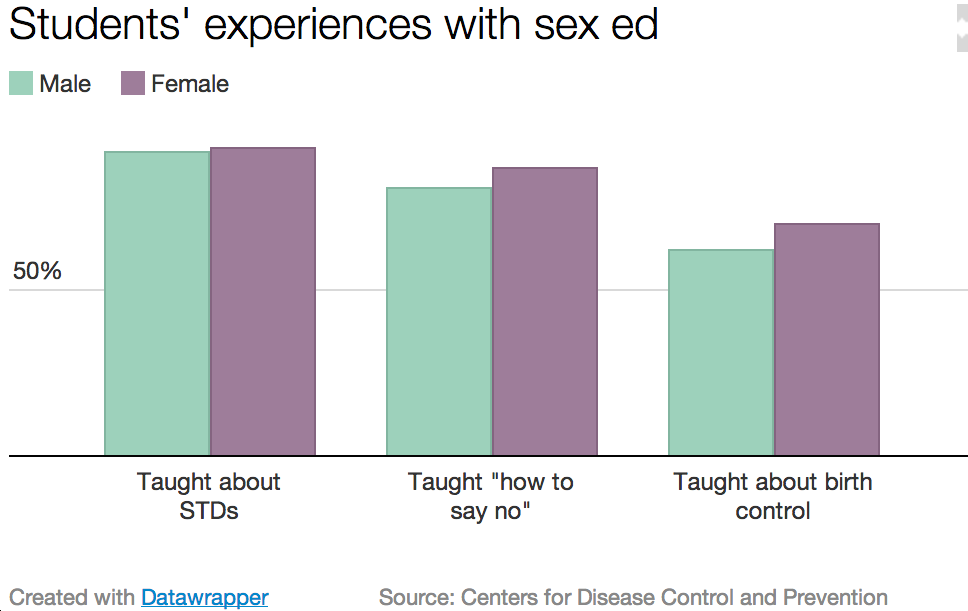

In a survey conducted from 2006 to 2008, almost all students said they learned about sexually transmitted diseases, but only 61 percent of male students had learned about birth control.

Research in the mid- to late 2000s slowed the abstinence-only movement. A 2007 federally funded study found students taking abstinence-only sex education classes started having sex around the same time as students from the same schools who did not take the classes. Abstinence-only education, it found, had no perceptible effects on whether students had sex, how many people they had sex with, whether they practiced safe sex, or their knowledge of birth control and its effectiveness.

In 2009, Congress effectively cut off federal funding for abstinence-only education, requiring that sex education programs be proven effective in order to get federal money. (A year later, Congress authorized $50 million for abstinence-only sex education as part of the health care overhaul.)

'Comprehensive' sex education

Activists from the World AIDS Day Coalition march to the White House in 2003 to protest abstinence-only sex education. The programs eventually fell out of favor in Congress. Brendan Smialowski/Getty Images

The groups that formed the Future of Sex Education had long opposed abstinence-only policies. They expected a surge in state interest as officials began retooling curriculums to qualify for federal grants under the new criteria, which favored "comprehensive sex education."

Comprehensive sex education is often presented as the mirror image of abstinence-only: teach about condoms, not just chastity. But the standards interpret "comprehensive" much more broadly.

The National Sexuality Education Standards include plenty on contraception: eighth-graders should be able to discuss the effectiveness, risks and benefits of contraceptive methods, including abstinence; they should be able to describe how to use a condom; and they should be able to identify medically accurate information about emergency contraception.

High school seniors should be also to explain how emergency contraception works and understand laws about parenting, abortion and pregnancy. Abstinence is in there too: eighth-graders should be able to effectively communicate why they choose not to engage in sex.

But most of the standards don't actually deal with puberty or contraception. Instead, they're about healthy relationships, respect and safety.

In the National Sexuality Education Standards fifth-graders, for example, should understand the romantic concept of sexual orientation; eighth-graders should be able to distinguish between sexual orientation, gender expression, and gender identity. By twelfth grade, they should "advocate for school policies and programs that promote dignity and respect for all."

Eighth-graders should be able discuss "bullying, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, sexual assault, incest, rape, and dating violence" and "explain why someone who has been raped or sexually assaulted is not at fault."

"If all we cared about is that young people didn't have babies too soon, we could give everybody a chastity belt," Hauser says. "What we're trying to do is provide them with information and skills."

An uphill battle

When abstinence-only education lost its federal funding, the moment seemed just right. But there was also something very wrong about the timing: it was right when another set of proposed national standards, Common Core, were becoming controversial.

What commotion the National Sexuality Education Standards have attracted has been from groups who link them to the Common Core. ("This is sex education on steroids," an anti-Common Core group wrote, warning that the reading and math standards start a slippery slope to standardized sex education.) In other words: sex ed has been less controversial, so far, than math and language arts.

The two movements aren't linked. The Common Core standards were developed by governors and state education officials, and have been adopted much more widely, in part because the Education Department promoted them.

But other national standards movements have been caught in the backlash. Several states are considering bills to change the process for adopting new state standards. Those bills would get the legislature involved in academic standards, rather than state education officials — and make statewide adoption of the sex education standards much less likely.

This leaves the sex-education landscape a patchwork of different policies. Nineteen states require sex education to include information on contraception. (A few are states that also require emphasizing the importance of abstinence until marriage. Sex education is full of contradictions.)

For now, their advocates say they work best at providing guidance to districts and states on how their own standards measure up.

"It would be surprising to me if one curriculum could meet the needs of every student across this country," Hauser says. "The standards, like all of these standards, are not saying how you should teach, but what young people need to know. They need to know the names of their body parts. They need to know what constitutes a healthy relationship."

One state, Colorado, has come closest to putting the standards' vision in action. Gov. John Hickenlooper signed a bill in 2013 creating a new grant program for comprehensive sex education programs. Districts that received the grants would have had to abide by new standards that looked a lot like the national version: they were sensitive to LGBT students and focused on safety and respect as well as contraception.

The bill inspired fierce debate — "This is not about sex education, this is about an agenda of the left to promote gay and lesbian sex education," said one Republican lawmaker, according to Chalkbeat Colorado.

In the end, the grant program wasn't funded, says Mark Salley, a spokesman for the Colorado Department of Health.

The standards' proponents' hopes now lie in Miami, where the school district is considering an overhaul of the sex education curriculum.

As schools and states try to shift to the evidence-based programs, they're finding gaping holes left by a decade of emphasizing abstinence, Hauser says.

"They can't talk about contraception because the young people don't know anything about reproduction or anatomy," she says. "They start to talk about how barrier methods work, but young people don't know what the cervix is."